Density

The density of a material is defined as its mass per unit volume. The symbol of density is ρ (the Greek letter rho). The density of a substance is the reciprocal of its specific volume, a representation commonly used in thermodynamics.

In some cases (for instance, in the United States oil and gas industry), density is also defined as its weight per unit volume [1].

Contents |

Formula

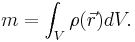

Mathematically, density is defined as mass divided by volume:

where:

(rho) is the density,

(rho) is the density, is the mass,

is the mass, is the volume.

is the volume.

Different materials usually have different densities, so density is an important concept regarding buoyancy, metal purity and packaging.

In some cases density is expressed as the dimensionless quantities specific gravity (SG) or relative density (RD), in which case it is expressed in multiples of the density of some other standard material, usually water or air/gas.

History

In a well-known tale, Archimedes was given the task of determining whether King Hiero's goldsmith was embezzling gold during the manufacture of a golden wreath dedicated to the gods and replacing it with another, cheaper alloy.[2] Archimedes knew that the irregularly shaped wreath could be crushed into a cube whose volume could be calculated easily and compared with the mass; but the king did not approve of this. Baffled, Archimedes took a relaxing immersion bath and observed from the rise of the warm water upon entering that he could calculate the volume of the gold wreath through the displacement of the water. Allegedly, upon this discovery, he went running naked through the streets shouting, "Eureka! Eureka!" (Εύρηκα! Greek "I found it"). As a result, the term "eureka" entered common parlance and is used today to indicate a moment of enlightenment.

The story first appeared in written form in Vitruvius' books of architecture, two centuries after it supposedly took place.[3] Some scholars have doubted the accuracy of this tale, saying among other things that the method would have required precise measurements that would have been difficult to make at the time.[4][5]

Measurement of density

For a homogeneous object, the mass divided by the volume gives the density. The mass is normally measured with an appropriate scale or balance; the volume may be measured directly (from the geometry of the object) or by the displacement of a fluid. Hydrostatic weighing is a method that combines these two.

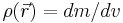

If the body is not homogeneous, then the density is a function of the position:  , where

, where  is an elementary volume at position

is an elementary volume at position  . The mass of the body then can be expressed as

. The mass of the body then can be expressed as

The density of a solid material can be ambiguous, depending on exactly how its volume is defined, and this may cause confusion in measurement. A common example is sand: if it is gently poured into a container, the density will be low; if the same sand is compacted into the same container, it will occupy less volume and consequently exhibit a greater density. This is because sand, like all powders and granular solids, contains a lot of air space in between individual grains. The density of the material including the air spaces is the bulk density, which differs significantly from the density of an individual grain of sand with no air included.

Common units

The SI unit for density is:

- kilograms per cubic metre (kg/m³)

Litres and metric tons are not part of the SI, but are acceptable for use with it, leading to the following units:

- kilograms per litre (kg/L)

- grams per millilitre (g/mL)

- metric tons per cubic metre (t/m³)

Densities using the following metric units all have exactly the same numerical value, one thousandth of the value in (kg/m³). Liquid water has a density of about 1 kg/dm³, making any of these SI units numerically convenient to use as most solids and liquids have densities between 0.1 and 20 kg/dm³.

- kilograms per cubic decimetre (kg/dm³)

- grams per cubic centimetre (g/cc, gm/cc or g/cm³)

- megagrams per cubic metre (Mg/m³)

In U.S. customary units density can be stated in:

- Avoirdupois ounces per cubic inch (oz/cu in)

- Avoirdupois pounds per cubic inch (lb/cu in)

- pounds per cubic foot (lb/cu ft)

- pounds per cubic yard (lb/cu yd)

- pounds per U.S. liquid gallon (lb/gal)

- pounds per U.S. bushel (lb/bu)

- slugs per cubic foot.

In principle there are Imperial units different from the above as the Imperial gallon and bushel differ from the U.S. units, but in practice they are no longer used, though found in older documents. The density of precious metals could conceivably be based on Troy ounces and pounds, a possible cause of confusion.

Changes of density

In general, density can be changed by changing either the pressure or the temperature. Increasing the pressure will always increase the density of a material. Increasing the temperature generally decreases the density, but there are notable exceptions to this generalization. For example, the density of water increases between its melting point at 0 °C and 4 °C; similar behaviour is observed in silicon at low temperatures.

The effect of pressure and temperature on the densities of liquids and solids is small. The compressibility for a typical liquid or solid is 10−6 bar−1 (1 bar=0.1 MPa) and a typical thermal expansivity is 10−5 K−1.

In contrast, the density of gases is strongly affected by pressure. The density of an ideal gas is

where

is the molar mass

is the molar mass is the pressure

is the pressure is the universal gas constant

is the universal gas constant is the absolute temperature.

is the absolute temperature.

This means that the density of an ideal gas can be doubled by doubling the pressure, or by halving the absolute temperature.

Osmium is the densest known substance at standard conditions for temperature and pressure.

Density of water (at 1 atm)

- See also: Water density

| Temp (°C) | Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|

| 100 | 958.4 |

| 80 | 971.8 |

| 60 | 983.2 |

| 40 | 992.2 |

| 30 | 995.6502 |

| 25 | 997.0479 |

| 22 | 997.7735 |

| 20 | 998.2071 |

| 15 | 999.1026 |

| 10 | 999.7026 |

| 4 | 999.9720 |

| 0 | 999.8395 |

| −10 | 998.117 |

| −20 | 993.547 |

| −30 | 983.854 |

| The density of water in kilograms per cubic metre (SI unit) at various temperatures in degrees Celsius. The values below 0 °C refer to supercooled water. |

|

Density of air (at 1 atm)

| T in °C | ρ in kg/m3 |

|---|---|

| –25 | 1.423 |

| –20 | 1.395 |

| –15 | 1.368 |

| –10 | 1.342 |

| –5 | 1.316 |

| 0 | 1.293 |

| 5 | 1.269 |

| 10 | 1.247 |

| 15 | 1.225 |

| 20 | 1.204 |

| 25 | 1.184 |

| 30 | 1.164 |

| 35 | 1.146 |

Density of solutions

The density of a solution is the sum of mass (massic) concentrations of the components of that solution.

Mass (massic) concentration of a given component ρi in a solution can be called partial density of that component.

Densities of various materials

| Material | ρ in kg/m3 | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Interstellar medium | 10−25 − 10−15 | Assuming 90% H, 10% He; variable T |

| Earth's atmosphere | 1.2 | At sea level |

| Aerogel | 1 − 2 | |

| Styrofoam | 30 − 120 | From |

| Cork | 220 − 260 | From |

| Water (fresh) | 1000 | At STP |

| Water (salt) | 1030 | |

| Plastics | 850 − 1400 | For polypropylene and PETE/PVC |

| Glycerol[6][7] | 1261 | |

| The Earth | 5515.3 | Mean density |

| Iron | 7874 | Near room temperature |

| Copper | 8920 − 8960 | Near room temperature |

| Lead | 11340 | Near room temperature |

| The Inner Core of the Earth | ~13000 | As listed in Earth |

| Uranium | 19100 | Near room temperature |

| Tungsten | 19250 | Near room temperature |

| Gold | 19300 | Near room temperature |

| Platinum | 21450 | Near room temperature |

| Iridium | 22500 | Near room temperature |

| Osmium | 22610 | Near room temperature |

| The core of the Sun | ~150000 | |

| White dwarf star | 1 × 109[8] | |

| Atomic nuclei | 2.3 × 1017 [9] | Does not depend strongly on size of nucleus |

| Neutron star | 8.4 × 1016 − 1 × 1018 | |

| Black hole | 4 × 1017 | Mean density inside the Schwarzschild radius of an Earth-mass black hole (theoretical) |

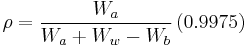

Density of composite material

In the United States, ASTM specification D792-00[10] describes the steps to measure the density of a composite material.

where:

is the density of the composite material, in g/cm3

is the density of the composite material, in g/cm3

and

is the weight of the specimen when hung in the air

is the weight of the specimen when hung in the air is the weight of the partly immersed wire holding the specimen

is the weight of the partly immersed wire holding the specimen is the weight of the specimen when immersed fully in distilled water, along with the partly immersed wire holding the specimen

is the weight of the specimen when immersed fully in distilled water, along with the partly immersed wire holding the specimen is the density in g/cm3 of the distilled water at 23 °C.

is the density in g/cm3 of the distilled water at 23 °C.

See also

- List of elements by density

- Charge density

- Buoyancy

- Bulk density

- Dord

- Energy density

- Lighter than air

- Number density

- Orthobaric density

- Specific weight

- Spice (oceanography)

- Standard temperature and pressure

- Orders of magnitude (density)

- Density prediction by the Girolami method

References

- ↑ http://oilgasglossary.com/density.html

- ↑ Archimedes, A Gold Thief and Buoyancy - by Larry "Harris" Taylor, Ph.D.

- ↑ Vitruvius on Architecture, Book IX, paragraphs 9-12, translated into English and in the original Latin.

- ↑ The first Eureka moment, Science 305: 1219, August 2004.

- ↑ Fact or Fiction?: Archimedes Coined the Term "Eureka!" in the Bath, Scientific American, December 2006.

- ↑ glycerol composition at physics.nist.gov

- ↑ Glycerol density at answers.com

- ↑ Extreme Stars: White Dwarfs & Neutron Stars, Jennifer Johnson, lecture notes, Astronomy 162, Ohio State University. Accessed on line May 3, 2007.

- ↑ Nuclear Size and Density, HyperPhysics, Georgia State University. Accessed on line June 26, 2009.

- ↑ (2004). Test Methods for Density and Specific Gravity (Relative Density) of Plastics by Displacement. ASTM Standard D792-00. Vol 81.01. American Society for Testing and Materials. West Conshohocken. PA.

External links

- Glass Density Calculation - Calculation of the density of glass at room temperature and of glass melts at 1000 - 1400°C

- List of Elements of the Periodic Table - Sorted by Density

- Calculation of saturated liquid densities for some components

- On-line calculator for densities and partial molar volumes of aqueous solutions of some common electrolytes and their mixtures, at temperatures up to 323.15 K.

- Water - Density and Specific Weight

- Temperature dependence of the density of water - Conversions of density units

- A delicious density experiment